"Regenerative design can bring a river back to life. It can restore the health and vitality of an individual and their family. It can transform grief and trauma into vital pathways of healing for people, community, and ecosystems. Combining Indigenous lifeways with the best scientific knowledge about human behaviour, cultural evolution, and the dynamic Earth, a path can be made by walking it throughout the rest of this century and beyond."

Joe Brewer

This page is being updated. Here's a sneak peek…

7-Generation GTB is growing a metaphorical Tree of Life through social and ecological regeneration for ecopsychosocial wellbeing (people, community, planet). We are living into a story of Bioregional Earth. The underlying dynamics are bioregional and intergenerational.

The "fuzzy boundary" of the GTB (Greater Tkaronto Bioregion) appears above. The GTB is 3 million hectares, 10 million people (about a quarter of Canada's population), on the north shore of Lake Ontario.

Bioregions are emerging around the planet, with many learning together in the Design School for Regenerating Earth co-founded by global regeneration leader Joe Brewer.

The international Earth Charter begins with a sense of urgency:

"We stand at a critical moment in Earth's history,

a time when humanity must choose its future…

It is imperative that we, the peoples of Earth, declare our responsibility to one another, to the greater community of life, and to future generations… Fundamental changes are needed in our values, institutions, and ways of living. We must realize that when basic needs have been met, human development is primarily about being more, not having more… Life often involves tensions between important values. This can mean difficult choices. However, we must find ways to harmonize diversity with unity, the exercise of freedom with the common good, short-term objectives with long-term goals… Everyone shares responsibility for the present and future well-being of the human family and the larger living world… Every individual, family, organization, and community has a vital role to play."

Our challenge is planetary. Our path forward is through bioregions, the smallest actionable scale that reflects planetary processes. Bioregions are indeed the difference that may make a difference.

THE DESIGN PATHWAY

Bioregional regeneration is explored by Joe Brewer in his book The Design Pathway for Regenerating Earth.

Every bioregion is unique in its context, with bioregions designing locally while learning from each other globally.

In a powerful North/South collaboration, GTB will prototype real-world action together with Brewer's living laboratory in the 500,000 hectare bioregion around Barichara, Colombia.

Nestled high in the mountains of Colombia, Barichara is home to a population of 7,000. It's registered as a national monument, with beautiful vistas and classic local architecture.

Located in the heart of Indigenous Guane territory, it's the only "High Andes" tropical dry forest on Earth.

There is a network of small landowner farms providing food to the town, which depends on tourism. Many of the river systems have dried up. The area currently has a serious water shortage. More than 90% of the native forest was destroyed to make room for monoculture crops like tobacco, beans, and squash.

There are a number of regenerative projects already happening. The Barichara work includes development of a Bioregional Learning Center, a Tapestry of Projects for integrated landscape management, and a Territorial Foundation. Find out more in this video with Joe Brewer.

Adapting for the Canadian, urban/rural context of the GTB, we're using intergenerational and bioregional dynamics for ecopyschosocial wellbeing. Particularly in the context of a WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industrial, Rich, Democratic) society, we must #ChangeTheStory of who we are, what we value, and how we live with each other on a rapidly changing planet.

The ultimate goal of a bioregional approach is a fractally scale-linked network of activated bioregions around the planet. If these numbered in the hundreds, cumulatively they could reach a critical mass to regenerate the entire Earth.

THE FUTURE IS BIOREGIONAL

What the heck is a bioregion? As this video explains, it's an understandable scale at which we can be more aware of and live into the interrelatedness of all life around us.

There are different definitions of the word "bioregion." In fact, one article claims to have uncovered 22 different definitions of the word. If that's the case, we certainly need to clearly explain our meaning whenever we use the term.

Some limit the term to include only plants and animals. But bioregions aren't the same as "ecoregions." Ecoregions, as defined by the World Wildlife Fund or the Commission for Environmental Cooperation, are scientifically-based and focus on wildlife and vegetation. Some argue the focus on plants and animals is the dominant use of the word bioregion, justifying this narrow definition by frequency of use in Western scientific literature. But quantity of use in scientific literature is skewed by both paradigm and funding opportunities.

The prefix bio comes from the Greek, meaning "life." Environmental writer and bioregional advocate Peter Berg described a bioregion as your "life place" – the place in which you live your life and which gives you life. That's very distinct from political boundaries or ecoregions defined by ecology. A bioregion recognizes people in place, with each influencing the other.

A bioregion includes all life in a place, which includes human beings. If humans can exert such influence over the entire planet as to have an epoch named after them, the Anthropocene, then to exclude them from a bioregion is to miss a vital piece of the puzzle. Humans, and the cultures they create, do indeed affect any given place on Earth – currently often for worse, but possibly for better if we can (re)learn how to be stewards of our place, as many Indigenous cultures did for millennia.

As is pointed out in the What is a Bioregion? exploration, "People matter. Ultimately, it is up to the people and inhabitants of a bioregion to determine what stewardship frameworks make sense for that area, what best represents them, and their way of life and living."

Bioregions can come in all shapes and sizes, and may shift and evolve over time. For example, the GTB (Greater Tkaronto Bioregion) is

Some claim to have the definitive "map" of bioregions around the world. The truth is – there is no map of bioregions. Like the story of Bioregional Earth itself, they're emerging – each from their own unique place

defined by geology, ecology, and culture (including Indigenous history).

From What is a Bioregion?: "A bioregion is defined as the largest physical boundaries where connections based on that place will make sense… [It's] defined along watershed and hydrological boundaries. It uses a combination of bioregional layers, beginning with the oldest 'hard' lines: geology, topography, tectonics, wind, fracture zones, and continental divides, working its way through the 'soft' lines: living systems such as soil, ecosystems, climate, marine life, and flora and fauna, and lastly the 'human' lines: human geography, energy, transportation, agriculture, food, music, language, history, Indigenous cultures, and ways of living within the context set into a place."

Based on earth systems science, the bioregion is the smallest scale that reflects planetary processes. It's only from the bioregion that you can meaningfully fractally scale-link impact.

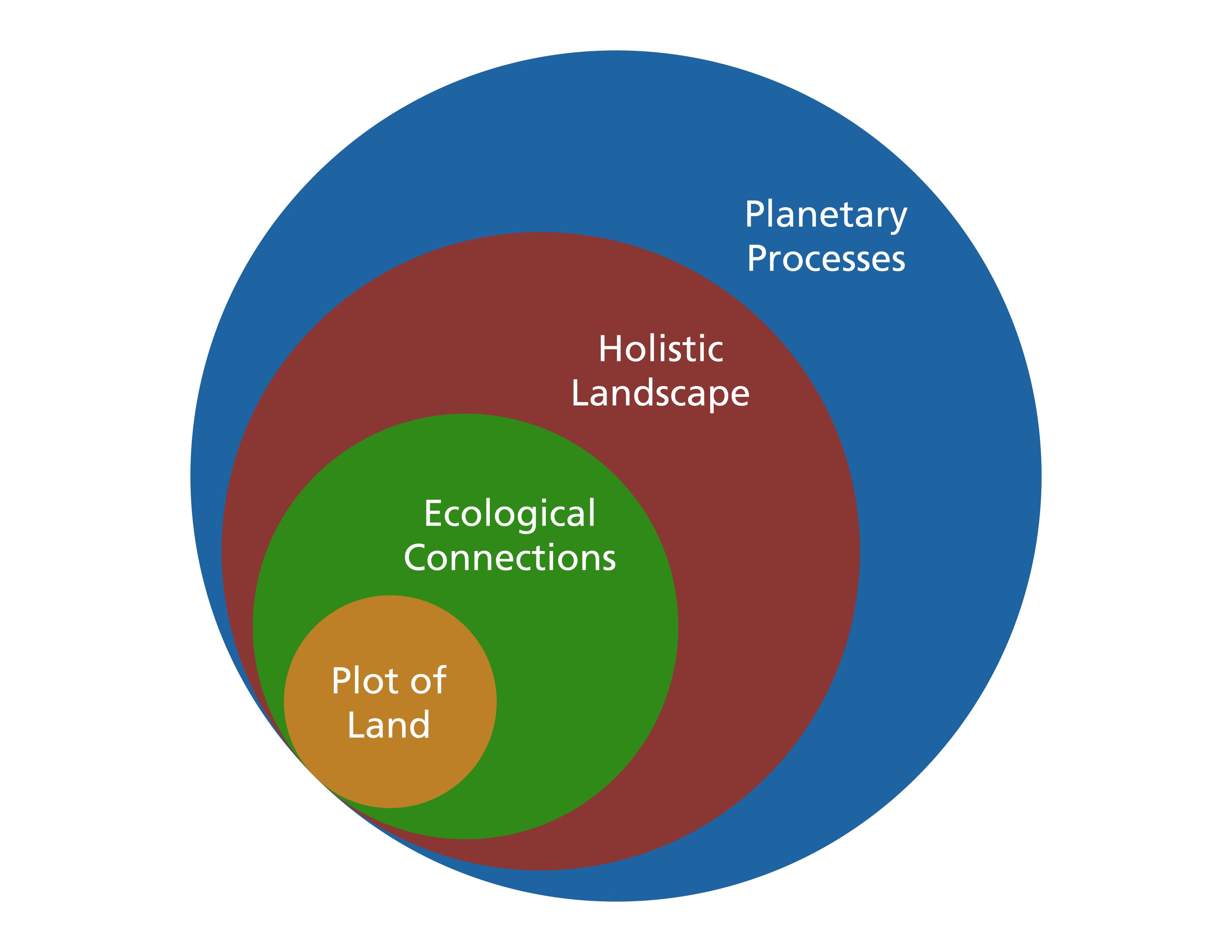

When the focus is the bioregion, then one person's backyard makes more sense in the larger story – and activities/projects coordinated across the bioregion have more positive effect. How does a plot of land (e.g. community garden, farm, park, forest) relate to the ecology around it (e.g. the river that might run through it) relate to the bioregion (defined by geography, ecology, culture, history) which ultimately relates to planetary processes (e.g. meandering and kinking jet stream, patterns of heat and drought)? Understanding the nested system of relationships and patterns supports deeper learning and can give everything more meaningful long-term effect.

Learning about our bioregion is vital, which is why a Bioregional Learning Center is a keystone structure. We can learn how to "partner" with our life place, which includes "restoration and maintenance of natural features to whatever extent is immediately possible; developing sustainable means to satisfy basic human needs; and support for living in place in the widest possible range of ways from economics and culture to politics and philosophy." The concept of a bioregion goes beyond the usual work of "conservation" and "environmentalism" to meet the challenges of our time.

GREATER TKARONTO BIOREGION

For the GTB, or Greater Tkaronto Bioregion, we're specifically using the Indigenous name for what's now known as Toronto to reflect the long human history of this place on the planet. Most scholars now agree that the city's name comes from the Mohawk word tkaronto, which means "where there are trees in the water." Clearly, the land meets the waters of Lake Ontario, and trees flourished in the many waterways of the Oak Ridges Moraine. Further, "as many as 4,500 years ago, native people drove stakes into the water to create fish weirs – enclosures – to catch fish as they swam through Atherley Narrows, where the water moves quickly as it flows between Lake Couchiching and Lake Simcoe. This continued for centuries, and was so successful that the place was considered sacred, a spot where the creator had guaranteed a bountiful source of food."

There were Indigenous trails going through this place. One of the most well-known is the nearly 50 km-long footpath today called the Carrying Place Trail. This was an ancient portage trail that ran northward along the banks of the Humber River as far as Lake Simcoe.

Indigenous use of the watersheds along the north shore of Lake Ontario goes back further than the pyramids. Humans began to migrate into this area following the last ice age, about 12,500 years ago. Archaeological evidence indicates the first inhabitants were the Paleo Indians who moved into the Toronto region after the glaciers retreated.

Much of the GTB is in the Carolinian forest zone. The forests in this zone are mixed, but broad-leaved deciduous trees dominate. This is the smallest forest region in Canada, at just 0.25% of the country's landmass. Yet the Carolinian forests are home to over 40% of Canada's native plants, 50% of Canada's birds, and 66% of our reptiles. It's one of our most biologically diverse ecological regions.

The Carolinian zone is the northernmost edge of the deciduous forest region in eastern North America, and is named after the American Carolina states. The climate of the Canadian portion of the region has the warmest annual temperatures, the longest frost-free seasons, and the mildest winters in Ontario.

In defining the "fuzzy boundary" of the GTB, we draw on the seminal 1992 Regeneration report by The Honourable David Crombie (Mayor of Toronto 1972-1978; PC Member of Parliament 1978-1988; President and CEO of the Canadian Urban Institute 2001-2007).

Some information from the Interim and Final Reports…

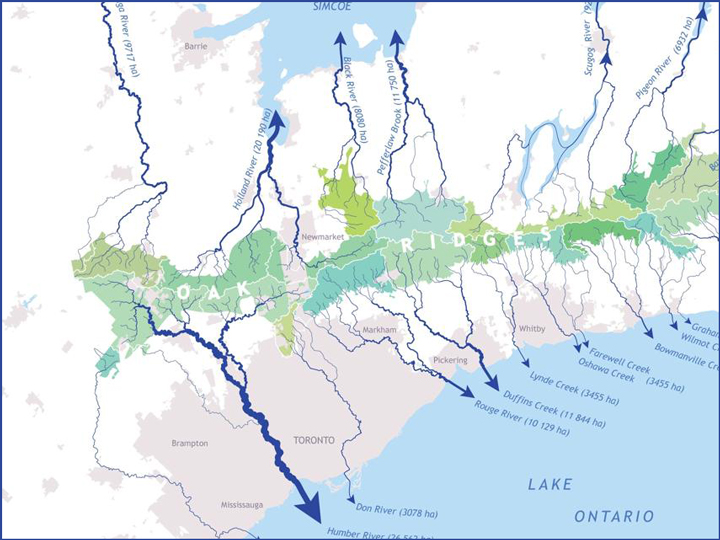

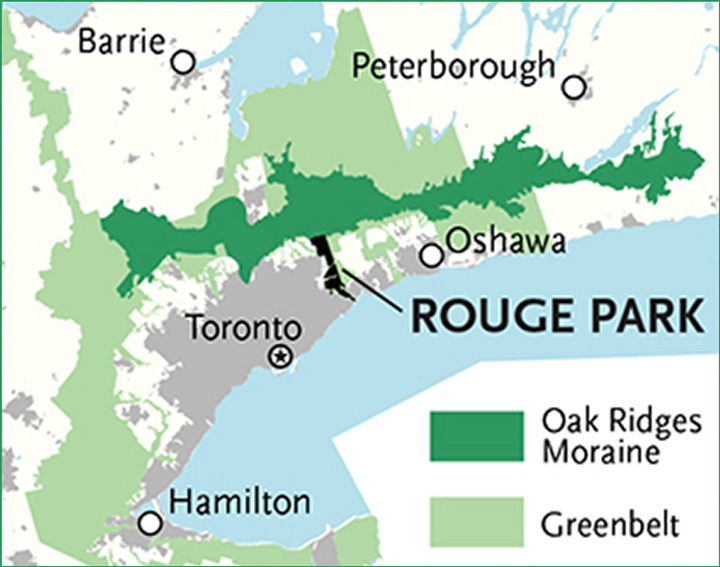

The GTB is generally "bounded by the Niagara Escarpment on the west, the Oak Ridges Moraine to the north (along with Lake Simcoe) and east, and Lake Ontario to the south. The lands and waters in this bioregion share climatic and many ecological similarities. The soils and landforms are based on the glacial deposits of the Lake Ontario plain as it rises from the shores of the lake to meet the gravelly hills of the Oak Ridges Moraine. The watersheds arising in the moraine drain southwards to Lake Ontario and northwards to lakes Simcoe and Scugog. Most of the bioregion now falls within the commuter and economic orbit of Toronto. In this sense it is our home – the bioregion in which we live, work, and play." This is the "heart" of the GTB, with all the life-giving arteries. We even have a

The Niagara Escarpment is a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve. It stretches 725 km from Lake Ontario (near Niagara Falls) to the tip of the Bruce Peninsula (between Georgian Bay and Lake Huron). The Escarpment corridor crosses two major biomes: boreal needle leaf forests in the north and temperate broadleaf forest in the south. Its habitats range over more than 430 m in elevations and include Great Lakes coastlines, cliff edges, talus slopes, wetlands, woodlands, limestone alvar pavements, oak savannahs, conifer swamps, and many others. It has 300 bird species,

The Oak Ridges Moraine is also a very special local land feature. "The greatest natural force shaping the area was the retreat, starting about 15,000 years ago, of the Wisconsin Glaciers. As they slowly withdrew to end the last ice age, the glaciers carved out the rivers flowing north to Lake Simcoe, east to Lake Scugog, and south to Lake Ontario, and they left behind the fertile soils characteristic of much of the area. In the northern part of the bioregion, the retreating glaciers left in their path the hilly Oak Ridges Moraine, a unique formation of sand and gravel deposits. For thousands of years, rainwater has filtered downwards through the moraine, migrated laterally, and then discharged upwards to form wetlands – the headwaters of virtually all the rivers flowing south and north in the area. As the ice age loosened its frigid grip and temperatures rose, river valleys were flooded and fertile marshes developed at river mouths. Natural forces left us a unique, varied, and complex bioregion."

In David Crombie's words, the Oak Ridges Moraine is the rain barrel of the GTB; in Joe Brewer's words, it's the giant sponge of the GTB.

"There are 16 major rivers flowing into Lake Ontario in the Greater Toronto Bioregion, and approximately 66 river valley systems in the area. Although few of the river valley systems are in a totally natural state, they continue to fulfill important functions for human activity (including recreation) and as corridors or links for the movement of wildlife."

In his reports, Crombie states that the region is "both literally and figuratively, at a watershed. Not long ago, society believed that the environment was endlessly able to absorb the detritus of a modern, industrial-based economy. More recently, the assumption was that the environment and the economy were inevitably opposed: opting for one meant damaging the other. Today, however, it is clear that the two, rather than being mutually exclusive, are mutually dependent: a good quality of life and economic development cannot be sustained in an ecologically deteriorating environment. The way we choose to treat the Greater Toronto waterfront is crucial. If governments and individuals recognize – and act on – the need to resolve past environmental problems and forge strategies to protect the waterfront now and in the future, we will, indeed, have successfully crossed a watershed."

Here it's important to note that Toronto is on Lake Ontario, one of the five Great Lakes – the others are Superior, Michigan, Huron, and Erie. Although the Great Lakes don't physically touch, their waters all flow together in one big system. The Great Lakes are connected by close to 5,000 tributaries: a series of smaller lakes, rivers, streams, and straits flowing into larger bodies of water. Water in the Great Lakes comes from thousands of streams and rivers covering a watershed area of approximately 520,587 square kilometres (or 201,000 square miles). The flow of water in the Great Lakes system moves from one lake to another eastward, ultimately flowing into Lake Ontario and then into the St. Lawrence River out to the Atlantic Ocean. But, here's a surprising fact: the Great Lakes Basin is essentially a closed water system. Outflows from the Great Lakes are very small in comparison to their total volume; each year, less than 1% of the volume of the water in the Great Lakes flows out through the St. Lawrence River. The Great Lakes have 84% of North America's surface fresh water, and about 21% of the world's supply of surface fresh water.

The Great Lakes Basin has nearly 25% of Canadian agricultural production. 5% of Ontario is farmland, with all Class 1 and 2 farmland in the GTB.

About 185 First Nations, Métis, or Native American Tribes' communities reside and have traditional Territories and homelands around the Great Lakes Basin.

Included in the GTB is Rouge National Urban Park (primarily in Markham and Toronto), Canada's largest at 7,900 hectares. This protected, natural environment is easily accessible from the city. It includes forests, creeks, farms and trails as well as marshland, a beach on Lake Ontario, and human history spanning over 10,000 years. The Rouge National Urban Park is part of the legacy of David Crombie's 1992 report, as is the Greenbelt.

The Greenbelt protected lands cover over 800,000 hectares, encompassing the Niagara Escarpment, Oak Ridges Moraine, and nearly one million acres of prime farmland. The Greenbelt was created in 2005 to protect high-quality farmland and environmentally sensitive features like forests, lakes and species at risk from urban sprawl and development. Home to 5,500 farms, farmland makes up 43% of the Greenbelt. It's the world's largest greenbelt, and an international model of smart land use planning.

Crombie had a warning: "The Greater Toronto Bioregion has important natural assets: beaches, wetlands, and bluffs along the waterfront; deep, wooded river valleys; the moraine's rolling, pastoral hills; majestic rock cliffs along the Niagara Escarpment; cool trout streams; fertile soils for agriculture; and more. Despite these blessings, there are many signs of environmental, social, and economic stress in the region."

The region is complicated by the fact that it's "governed by several regional municipalities,

several dozen local municipalities, about a dozen conservation authorities, and numerous federal and provincial ministries, departments, boards, agencies, and commissions. In an era when it has become clear that governments cannot solve environmental, social, and economic problems by themselves, the thousands of businesses and [millions of] residents of the bioregion also have a role to play." As do Indigenous peoples and their rights on their traditional territories.

The boundaries of local Conservation Authorities, organized by watersheds, helped to define the fuzzy boundary of the GTB. Unique to Ontario, Conservation Authorities are local watershed management agencies that deliver services and programs to protect and manage impacts on water and other natural resources. There are 36 Conservation Authorities in Ontario, 13 of which are within the GTB. Those 13 are: Toronto and Region Conservation Authority (the largest), Credit Valley, Halton, Hamilton, Niagara Peninsula, Central Lake Ontario, Ganaraska, Lake Simcoe, Nottawasaga Valley, Kawartha, Otonabee, Lower Trent, and Grand River.

Conservation Authorities began to be established by municipalities and the province in the 1940s in response to severe flooding, deforestation and erosion problems in Ontario. A pivotal event was Hurricane Hazel in 1954. During the storm, winds reached 124 km/h and over 200 millimetres of rain fell in just 24 hours. 81 people died, nearly 1,900 families were left homeless, and damages were between $25 and $100 million (modern-day cost has been estimated at over $1 billion). This storm mobilized the need for managing Ontario's watersheds on a regional basis. The provincial government amended the Conservation Authorities Act to enable Conservation Authorities to acquire lands for recreation and conservation purposes, and to regulate that land for the safety of the larger community.

Crombie quotes from a 1985 book, Dwellers in The Land: The Bioregional Vision by L. Thomas: "Our deepest folly is the notion that we are in charge of the place, that we own it and can somehow run it. We are beginning to treat the earth as a sort of domesticated household pet, living in an environment invented by us, part kitchen garden, part park, part zoo. It is an idea we must rid ourselves of soon, for it is not so. It is the other way around. We are not separate beings. We are a living part of the Earth's life, owned and operated by the Earth, probably specialized for functions on its behalf that we have not yet glimpsed."

We have been wise and proactive in the past. As climate change accelerates in the context of a polycrisis, a bioregional approach is the wise and strategic way forward.

Drawing on the model developed by Commonland, a bioregional approach can include designating three distinct areas: Natural Zone, Combined Zone, and Economic Zone. The GTB already has a strong bioregional base for these three zones, with Conservation Authorites already organized by watersheds and the Greenbelt. The GTB can both lead and learn from other bioregions around the world, in particular those with a large existing urban footprint. Toronto is the fourth largest city in North America, after Mexico City, New York, and Los Angeles.

Crombie notes, "The bioregional approach is both a way of doing things and a way of thinking, a renewal of values and philosophy. It is not really a new concept: since time immemorial, Indigenous peoples around the world have understood their connectedness to the rest of the ecosystem – the land, water, air, and other life. But, under many influences, and over many centuries, our society has lost its awareness of our place in ecosystems and, with it, our understanding of how they function… In the words of Professor Bill Rees of the University of British Columbia, 'people must acquire in their bones a sense that violation of the biosphere is a violation of self'… A key to understanding our place is to recognize that everything is interconnected to everything else."

Crombie quotes a 1986 article on the Great Lakes Basin that draws in the idea of interconnection across time: "You are new, yet not new. The molecules in your body have been parts of other organisms and will travel to other destinations in the future. Right now, in your lungs, there is likely to be at least one molecule from the breath of every human being who has lived in the past 3,000 years; the air around you will be used tomorrow by deer, lake trout, mosquitoes, and maple trees. The same is true of water, sunshine, and minerals. Everything in the biosphere is shared."

He emphasizes that "thinking about the whole bioregion helps focus attention on the interdependencies and links that exist within it: between city and countryside, natural and cultural processes, water and land, economic activities and quality of life… We view regeneration as a healing process that restores and maintains environmental health, as well as anticipating and preventing future harm. This means striving to ensure that existing land uses and activities are adapted, and all new development is designed, to contribute to the health, diversity, and sustainability of the entire ecosystem."

Crombie concludes his 1992 report by saying, "There is an urgent need for regeneration of the entire Greater Toronto Bioregion to remediate environmental problems caused by past activities, to prevent further degradation, and to ensure that all future activities result in a net improvement in environmental health. In a region experiencing dramatic economic growth and rapid urbanization, it is crucial to heed the warning signs of ecosystem stress, so that the quality of life that attracted people here can be restored and maintained, for existing and future generations."

Check out this video that traces the Past, Present, and Future of the GTB. Helping people to see and understand the bioregion is critical. One of the most important parts of bioregional social and ecological regeneration is organizing a learning ecosystem, a Bioregional Learning Center, that coherently integrates everything taking place in the bioregion.

BIG PICTURE

From Carl Sagan: "Look… That's here. That's home. That's us. On it everyone you love, everyone you know, everyone you ever heard of, every human being who ever was, lived out their lives. The aggregate of our joy and suffering, thousands of confident religions, ideologies, and economic doctrines, every hunter and forager, every hero and coward, every creator and destroyer of civilization, every king and peasant, every young couple in love, every mother and father, hopeful child, inventor and explorer, every teacher of morals, every corrupt politician, every 'superstar,' every 'supreme leader,' every saint and sinner in the history of our species lived there – on a mote of dust suspended in a sunbeam… Our planet is a lonely speck in the great enveloping cosmic dark. In our obscurity, in all this vastness, there is no hint that help will come from elsewhere to save us from ourselves."

We need to ground ourselves in our place on this planet. The Blue Marble principles remind us that to "deal with the complexities of global issues and problems we need principles to guide us, not a rule book to tie us down. The principles direct us to view the world globally, holistically, and systemically. This means examining interconnections across the artificial boundaries of nation-states, sector silos, and narrowly identified issues."

Bioregional work is very much weaving work.

Drawing on Indigenous worldviews, "weaving is intergenerational, making deep ties visible between generations alive today and their far distant ancestors. Weaving is interspecies, reconnecting us to what makes us truly human – our membership in the community of life as a planetary process… Our collective challenge is to weave ourselves back into the fabric of life… We are the weavers, we are the woven-ones. We are the dreamers, we are the dream. It is now, when the future of all beings hangs by the frailest of threads… In invoking the archetype of the weaver we are connecting with ancient Indigenous wisdom from around the world."

The bioregional dynamic underlies all of the 7-Generation GTB work. We're working toward ecopsychosocial wellbeing grounded in the land. #ChangeTheStory.